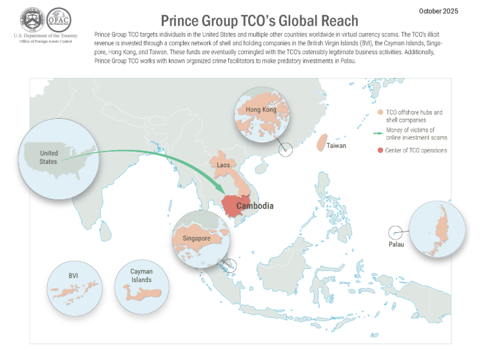

Cambodia, Mauritius, Taiwan, Singapore, Laos, and Palau were used to hide the Prince Group’s global $15 billion+ Pig butchering scams.

05/11/2025

In October 2025, the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) and the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), working closely with the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office (FCDO), took complementary actions against a major cybercriminal network operating out of Southeast Asia. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sb0278

Action taken

Here’s the current enforcement chain showing how the U.S. and U.K. coordinated actions against the Prince Group and Huione Group:

- OFAC Sanctions (U.S. Treasury)

- Action: Designated Prince Group as a Transnational Criminal Organisation (TCO) under IEEPA.

- Scope:

- 146 individuals and entities sanctioned, including Chen Zhi and affiliated companies.

- Blocked property and interests under U.S. jurisdiction; U.S. persons prohibited from dealings.

- Added crypto wallet addresses linked to Chen Zhi (holding $780 in BTC) to the SDN list. [home.treasury.gov], [finance.yahoo.com]

- Impact: Freezes assets globally where U.S. sanctions are enforced; cuts access to the U.S. financial system.

- FinCEN Section 311 Rule

- Action: Issued a final rule under Section 311 of the USA PATRIOT Act against Huione Group.

- Designation: Huione was identified as a “primary money laundering concern” for:

- Laundering $4B+ illicit proceeds, including $37M from North Korea cyber heists and pig-butchering scams.

- Operating subsidiaries like Huione Pay, Huione Crypto, and releasing its own “unfreezable” stablecoin (USDH). [fincen.gov], [chambers.com], [moneylaund…ngnews.com]

- Effect:

- U.S. banks prohibited from maintaining correspondent or payable-through accounts for Huione.

- Indirect access blocked—effectively exiling Huione from the global USD clearing system.

- UK FCDO Sanctions

- Action: Imposed complementary sanctions targeting Prince Group and related entities.

- Scope:

- Sanctioned six individuals and six entities, including Chen Zhi and Jin Bei Group (luxury hotel/casino operator linked to scam compounds).

- Targeted crypto exchanges like Byex Exchange, which processed $1.3B in illicit transactions. [crowdfundinsider.com], [regtechtimes.com]

- Impact: Aligns with OFAC measures, freezing assets in the UK and signalling risk to EU and Commonwealth jurisdictions.

- DOJ Criminal Action

- Action: Indicted Chen Zhi for wire fraud conspiracy and money laundering conspiracy.

- Asset Seizure:

- 127,271 BTC (~$15B) seized—the largest forfeiture in DOJ history.

- Funds traced to Prince Group’s mining operations and laundering network. [cnbc.com], [justice.gov]

How They Interlock

- OFAC → Freezes assets and blocks transactions globally.

- FinCEN → Cuts Huione’s lifeline to USD clearing, crippling laundering infrastructure.

- UK FCDO → Extends sanctions reach into Europe and Commonwealth jurisdictions.

- DOJ → Criminal prosecution + asset forfeiture, dismantling core financial resources.

Also, the UK has frozen significant assets and properties in London linked to Chen Zhi and the Prince Group as part of the joint sanctions with the U.S. Here’s what is confirmed:

Frozen London Assets

- £12 million mansion on Avenue Road, North London

- £100 million office building in the City of London (reported as 10 Fenchurch Street)

- 17 luxury flats across New Oxford Street and Nine Elms in South London

- Total portfolio: 19 properties worth over £100 million. [gov.uk], [therealdeal.com], [standard.co.uk], [comsuregroup.com], [sanctionssos.com]

Legal Basis

- UK sanctions under the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018, coordinated with OFAC measures.

- Targets: Chen Zhi, Prince Group, and affiliates (Jin Bei Group, Golden Fortune Resorts World Ltd, Byex Exchange).

Snap shot

- Seized Assets:

The U.S. Department of Justice has seized 127,271 BTC ( $15 billion) linked to Chen Zhi and the Prince Group. This is the largest crypto forfeiture in DOJ history. These funds are already in U.S. custody and were traced through a complex laundering network involving shell companies, casinos, and crypto mixers. [cnbc.com], [cbsnews.com], [justice.gov], [kbizoom.com] - Sanctions & Freezes:

OFAC imposed sweeping sanctions on 146 individuals and entities tied to the Prince Group Transnational Criminal Organisation (TCO). These sanctions freeze any assets under U.S. jurisdiction and block access to the U.S. financial system. FinCEN also severed Huione Group—a central hub for laundering—from U.S. banking channels under Section 311 of the USA PATRIOT Act. [home.treasury.gov], [siliconangle.com] - Jurisdictions Involved:

The Prince Group and its laundering network operated across Cambodia, Laos, Taiwan, Singapore, Mauritius, and Palau, among others. However, public sources do not specify exact amounts frozen in each country. The $15B seizure was primarily cryptocurrency held in wallets controlled by Chen Zhi and routed through multiple jurisdictions, including Laos-based mining operations and Asian shell companies. [kbizoom.com] - Still to Be Seized:

U.S. authorities indicate that additional assets—likely in the form of fiat funds, real estate, and luxury goods—are under investigation. Still, no official figures have been disclosed for the amount that remains to be seized. The sanctions aim to immobilise these assets globally, but enforcement depends on cooperation from local authorities in the listed countries. [home.treasury.gov]

The Prince Group

- The Prince Group was found to be operating a global online investment scam empire targeting American and international victims.

- What makes the Prince Group case so crucial is not just the amount of money involved, but the structure behind it.

- This wasn’t a loose network of opportunistic fraudsters; it was a fully integrated criminal business model, built to scale, shield itself from scrutiny, and generate billions in illicit revenue.

How the Crime Was Built: Fraud at an Industrial Scale

At its core, the operation relied on cyber-enabled investment scams. This kind has surged in recent years: fake trading platforms, crypto Ponzi schemes, romantic manipulation, and high-pressure “customer support” frauds. These scams were industrialised through the use of forced labour and the trafficking of victims.

Scam Compounds Disguised as Business Parks

The fraud was carried out physically in “scam compounds,” essentially office parks outfitted with call centre-like setups, where thousands of people were forced to commit online fraud.

These weren’t employees. They were trafficking victims, forced to commit Pig butchering scams: Long-game investment frauds where victims are “fattened up” through emotional manipulation and trust-building before being coerced into transferring funds into fraudulent platforms.

- Sextortion: Blackmail schemes using sexually explicit materials, often targeting minors.

- Romance fraud, phishing, and fake tech support: Often targeting lonely or vulnerable individuals, including minors.

- Crypto investment fraud: Fake apps or trading platforms that mimicked real financial services but routed funds to criminal wallets.

Each compound could have hundreds of enslaved workers operating under constant surveillance, coached in scripts, and evaluated based on how much money they brought in.

Reports documented torture, rape, and even killings in some of these locations, including within Jin Bei Group, a luxury hotel and casino brand under the Prince Group’s umbrella. This is how they found their victims:

Individuals were lured with fake job offers in customer service, tech, and finance.

- On arrival, passports and phones were confiscated, and movement was restricted.

- Victims were then forced to conduct scams, particularly pig butchering, which involves building false relationships to trick victims into investing in fake trading platforms.

- Multiple compounds operated under Jin Bei Group, a luxury hotel and casino operator tied directly to Prince Holding Group.

- Conditions inside the compounds included torture, sexual violence, isolation, extortion, and, in some cases, murder.

The Laundering Operation of Prince Group: Shell Companies, Offshore Fronts, and Crypto

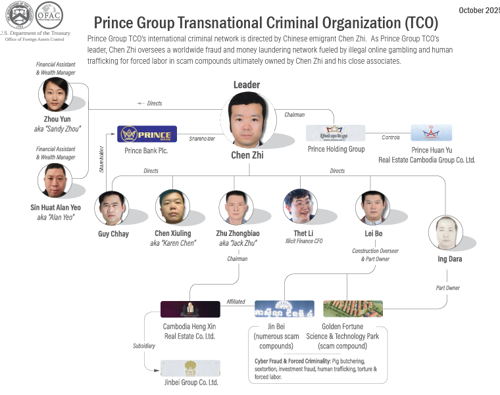

The Prince Group Transnational Criminal Organisation (TCO), led by Chen Zhi, built one of the most elaborate and damaging financial crime operations ever uncovered in Southeast Asia.

But unlike many criminal networks, this group didn’t operate in the shadows - it built a public-facing corporate empire designed to look legitimate while facilitating cyber scams, human trafficking, and industrial-scale money laundering.

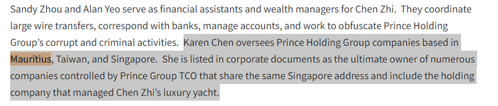

More specifically, the Prince Group TCO used over 100 shell and holding companies across Cambodia, Mauritius, Taiwan, Singapore, Laos, and Palau to facilitate the movement of funds and obscure their illicit origins. Most of these companies had no genuine commercial activity but appeared legitimate on paper - often sharing the same addresses and directors.

These entities were used to:

- Move money across jurisdictions with minimal regulatory scrutiny.

- Create the appearance of legitimate investment income and business operations.

- Reinvest proceeds into real estate, hospitality, and financial services, making it harder to isolate illicit capital from legal revenue.

This structure allowed the group to layer and integrate illicit funds without attracting attention, especially when paired with its legitimate business fronts.

Commercial Fronts That Looked Legitimate

The Prince Group’s greatest strength was its ability to blend criminal operations into a portfolio of real companies. These businesses gave the appearance of normal corporate growth while serving as key channels for laundering and reinvestment:

- Prince Bank Plc.: A licensed bank in Cambodia, used to manage internal flows of criminal proceeds and correspond with other financial institutions.

- Prince Huan Yu Real Estate Group: Involved in the construction and ownership of scam compounds under the guise of property development.

- Jin Bei Group Co. Ltd.: Casinos and hotels used as both fronts and locations for trafficking, fraud, and extortion operations.

- Golden Fortune Resorts World Co. Ltd.: A site publicly linked to torture and abuse of forced workers. This facility, near Phnom Penh, operated under the pretence of a technology park or resort development.

Each of these entities had public-facing legitimacy running marketing campaigns, engaging with governments, and presenting audited financials. This façade helped them avoid scrutiny for years while laundering billions in stolen funds.

Crypto as a Laundering Tool

Crypto played a central role. Through affiliates like Warp Data Technology Lao, the group operated a bitcoin mining operation to obscure the flow of stolen funds and convert them into traceable (yet difficult-to-seize) digital assets.

Huione Group, a Cambodia-based financial services firm, was central to this laundering process. It facilitated over $4 billion in illicit transactions, including:

$37 million in crypto from DPRK-linked cyber heists.

- $36 million from virtual currency investment scams.

- $300 million from other cyber scams.

By mixing crypto with fiat flows and routing funds through jurisdictions with weaker oversight, they maintained operational anonymity and scale.

Why It Worked for So Long

Understanding how this operation stayed afloat for over a decade requires us to look at three major blind spots:

- Jurisdictional Arbitrage

Prince Group’s core operations were in Cambodia, where regulatory oversight is limited and enforcement cooperation with international authorities is slow. The group then used offshore centres such as Mauritius, Singapore, and Palau to layer transactions and obscure beneficial ownership.

- Commingling Illicit and Legitimate Revenue

Chen Zhi’s empire was built on a hybrid model: launder illicit proceeds through legitimate-looking businesses. This made it difficult for investigators or financial institutions to detect anomalies, especially when these businesses paid taxes, employed staff, and engaged in plausible commercial activity.

- Exploitation of Financial Institutions

Entities like Prince Bank, nominally a commercial bank, played dual roles: fronting as a legitimate bank while being used internally to manage and obscure illicit flows. This insider access to the financial system allowed for wire transfers, account creation, and KYC manipulation that would be unavailable to outside actors.

CLOSE

The power and integrity of OFAC sanctions derive not only from OFAC’s ability to designate and add persons to the SDN List, but also from its willingness to remove persons from the SDN List consistent with the law.

The ultimate goal of sanctions is not to punish, but to bring about positive behavioural change. For information concerning the process for seeking removal from an OFAC list, including the SDN List, please refer to

- For more information on the persons designated today, click here. https://ofac.treasury.gov/recent-actions/20251014

- View the chart on the individuals and entities designated today. https://ofac.treasury.gov/media/934686/download?inline

- The final rule for Huione Group, as submitted to the Federal Register, can be found here. https://www.fincen.gov/news/news-releases/fincen-issues-final-rule-severing-huione-group-us-financial-system

- https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/10/16/2025-19571/imposition-of-special-measure-regarding-huione-group-as-a-foreign-financial-institution-of-primary

- https://www.cnbc.com/2025/10/14/bitcoin-doj-chen-zhi-pig-butchering-scam.html

- https://www.cbsnews.com/news/bitcoin-seizure-chen-zhi-pam-bondi-cambodia/

- https://www.justice.gov/usao-edny/pr/chairman-prince-group-indicted-operating-cambodian-forced-labor-scam-compounds-engaged

The Team

Meet the team of industry experts behind Comsure

Find out moreLatest News

Keep up to date with the very latest news from Comsure

Find out moreGallery

View our latest imagery from our news and work

Find out moreContact

Think we can help you and your business? Chat to us today

Get In TouchNews Disclaimer

As well as owning and publishing Comsure's copyrighted works, Comsure wishes to use the copyright-protected works of others. To do so, Comsure is applying for exemptions in the UK copyright law. There are certain very specific situations where Comsure is permitted to do so without seeking permission from the owner. These exemptions are in the copyright sections of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (as amended)[www.gov.UK/government/publications/copyright-acts-and-related-laws]. Many situations allow for Comsure to apply for exemptions. These include 1] Non-commercial research and private study, 2] Criticism, review and reporting of current events, 3] the copying of works in any medium as long as the use is to illustrate a point. 4] no posting is for commercial purposes [payment]. (for a full list of exemptions, please read here www.gov.uk/guidance/exceptions-to-copyright]. Concerning the exceptions, Comsure will acknowledge the work of the source author by providing a link to the source material. Comsure claims no ownership of non-Comsure content. The non-Comsure articles posted on the Comsure website are deemed important, relevant, and newsworthy to a Comsure audience (e.g. regulated financial services and professional firms [DNFSBs]). Comsure does not wish to take any credit for the publication, and the publication can be read in full in its original form if you click the articles link that always accompanies the news item. Also, Comsure does not seek any payment for highlighting these important articles. If you want any article removed, Comsure will automatically do so on a reasonable request if you email info@comsuregroup.com.